Below is a draft of the talk I’m giving next week at Austin for the first of three DH symposia this semester sponsored by the Texas Institute for Literary and Textual Studies. The theme of this first meeting is “Access, Authority, and Identity“; my paper is an attempt to think through some of the implications of working beyond the canon (however construed) for straight literary and cultural scholarship and for DH alike. It’s also a nice excuse to show a little preview of the geolocation work I’ve been doing recently.

A prettier PDF version is also available.

Undermining Canons

I have a point from which to start: Canons exist, and we should do something about them.

I wouldn’t have thought this was a dicey claim until I was scolded recently by a senior colleague who told me that I was thirty years out of date for making it. The idea being that we’d had this fight a generation ago, and the canon had lost. But I was right and he, I’m sorry to say, was wrong. Ask any grad student reading for her comps or English professor who might confess to having skipped Hamlet. As I say, canons exist. Not, perhaps, in the Arnoldian–Bloomian sense of the canon, a single list of great books, and in any case certainly not the same list of dead white male authors that once defined the field. But in the more pluralist sense? Of books one really needs to have read to take part in the discipline? And of books many of us teach in common to our own students? Certainly. These are canons. They exist.

So why, a few decades after the question of canonicity as such was in any way current, do we still have these things? If we all agree that canons are bad, why haven’t we done away with them? Why do we merely tinker around the edges, adding a Morrison here and subtracting a Dryden there? Is this a problem? If so, what are we going to do about it? And more to the immediate point, what does any of this have to do with digital humanities?

The answer to the first question—“Why do we still have canons?”—is as simple to articulate as it is apparently difficult to solve. We don’t read any faster than we ever did, even as the quantity of text produced grows larger by the year. If we need to read books in order to extract information from them and if we need to have read things in common in order to talk about them, we’re going to spend most of our time dealing with a relatively small set of texts. The composition of that set will change over time, but it will never get any bigger. This is a canon. [Footnote: How many canons are there? The answer depends on how many people need to have read a given set of materials in order to constitute a field of study. This was once more or less everyone, but then the field was also very small when that was true. My best guess is that the number is at least a hundred or more at the very lowest end—and an order of magnitude or two more than that at the high end—which would give us a few dozen subfields in English, give or take. That strikes me as roughly accurate.]

Another way of putting this would be to say that we need to decide what to ignore. And the answer with which we’ve contented ourselves for generations is: “Pretty much everything ever written.” We don’t read much. What little we do read is deeply nonrepresentative of the full field of literary and cultural production. Our canons are assembled haphazardly, with a deep set of ingrained cultural biases that are largely invisible to us, and in ignorance of their alternatives. We’re doing little better, frankly, than we were with the dead-white-male bunch fifty or a hundred years ago, and we’re just as smug in our false sense of intellectual scope.

So canons, even in their current, mildly multiculturalist form, are an enormous problem, one that follows from our single working method, that is, from the need to perform always and only close reading as a means of cultural analysis. It’s probably clear where I’m going with this, at least to a group of DH folks. We need to do less close reading and more of anything and everything else that might help us extract information from and about texts as indicators of larger cultural issues. That includes bibliometrics and book historical work, data-mining and quantitative text analysis, economic study of the book trade and of other cultural industries, geospatial analysis, and so on. Moretti is an obvious model here, as is the work of people like Michael Witmore on early modern drama and Nicholas Dames on social structures in nineteenth-century fiction.

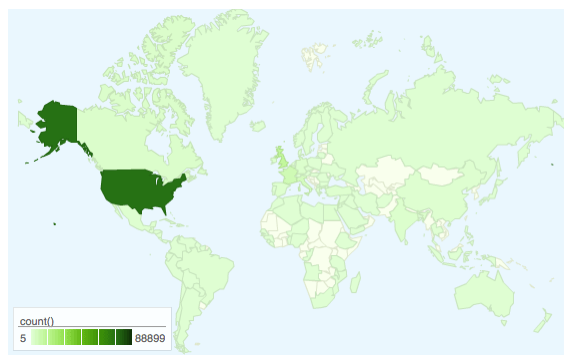

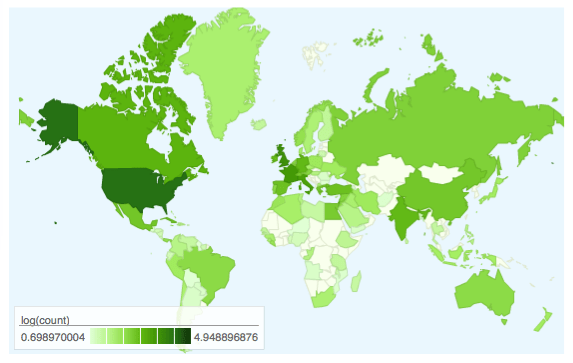

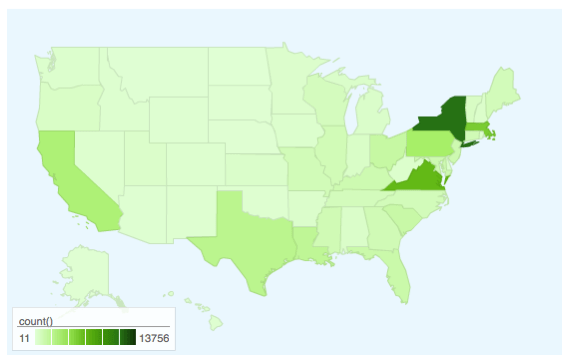

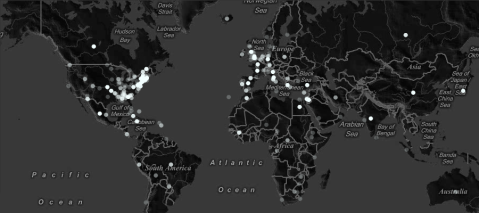

To show you one quick example of what I have in mind, here’s a map of the locations mentioned in thirty-seven American literary texts published in 1851:

Figure 1: Places named in 37 U.S. novels published in 1851

There are some squarely canonical works included in this collection, including Moby-Dick and House of the Seven Gables, but the large majority are obscure novels by the likes of T. S. Arthur and Sylvanus Cobb. I certainly haven’t read many of them, nor am I likely to spend months doing so. The corpus is drawn from the Wright American Fiction collection and represents about a third of the total American literary works published that year. [Footnote: Why only a third? Those are all the texts available in machine-readable format at the moment.] Place names were extracted using a tool called GeoDict, which looks for strings of text that match a large database of named locations. I had to do a bit of cleanup on the extracted places, mostly because many personal names and common adjectives are also the names of cities somewhere in the world. I erred on the conservative side, excluding any of those I found and requiring a leading preposition for cities and regions, so if anything, I’ve likely missed some valid places. But the results are fascinating. Two points of interest, just quickly:

- For one, there are a lot more international locations than one might have expected. True, many of them are in Britain and western Europe, but these are American novels, not British reprints, so even that fact might surprise us. And there are also multiple mentions of locations in South America, Africa, India, China, Russia, Australia, the Middle East, and so on. The imaginative landscape of American fiction in the mid-nineteenth century appears to be pretty diversely outward looking in a way that hasn’t received much attention.

- And then—point two—there’s the distinct cluster of named places in the American south. At some level this probably shouldn’t be surprising; we’re talking about books that appeared just a decade before the Civil War, and the South was certainly on people’s minds. But it doesn’t fit very well with the stories we currently tell about Romanticism and the American Renaissance, which are centered firmly in New England during the early 1850s and dominate our understanding of the period. Perhaps we need to at least consider the possibility that American regionalism took hold significantly earlier than we usually claim.

So as I say, I think this is a pretty interesting result, one that demonstrates a first step in the kind of analyses that remain literary and cultural but that don’t depend on close reading alone nor suffer the material limits such reading imposes. I think we should do more of this—not necessarily more geolocation extraction in mid-nineteenth-century American fiction (though what I just showed obviously doesn’t exhaust that little project), but certainly more algorithmic and quantitative analysis of piles of text much too large to tackle “directly.” (“Directly” gets scare quotes because it’s a deeply misleading synonym for close reading in this context.)

If we do that—shift more of our critical capacity to such projects—there will be a couple of important consequences. For one thing, we’ll almost certainly become worse readers. Our time is finite; the less of it we devote to an activity, the less we’ll develop our skill in that area. Exactly how much our reading suffers—and how much we should care—are matters of reasonable debate; they depend on both the extent of the shift and the shape of the skill–experience curve for close reading. My sense is that we’ll come out alright and that it’s a trade well worth making. We gain a lot by having available to us the kinds of evidence text mining (for example) provides, enough that the outcome will almost certainly be a net positive for the field. But I’m willing to admit that the proof will be in the practice and that the practice is, while promising, as yet pretty limited. The important point, though, is that the decay of close reading as such is a negative in itself only if we mistakenly equate literary and cultural analysis with their current working method.

Second—and maybe more important for those of us already engaged in digital projects of one sort or another—we’ll need to see a related reallocation of resources within DH itself. Over the last couple of decades, many of our most visible projects have been organized around canonical texts, authors, and cultural artifacts. They have been motivated by a desire to understand those (quite limited) objects more robustly and completely, on a model plainly derived from conventional humanities scholarship. That wasn’t a mistake, nor are those projects without significant value. They’ve contributed to our understanding of, for example, Rossetti and Whitman, Stowe and Dickinson, Shakespeare and Spenser. And they’ve helped legitimate digital work in the eyes of suspicious colleagues by showing how far we can extend our traditional scholarship with new technologies. They’ve provided scholars around the world—including those outside the centers of university power—with better access to rare materials and improved pedagogy by the same means. But we shouldn’t ignore the fact that they’ve also often been large, expensive undertakings built on the assumption that we already know which authors and texts are the proper ones to which to devote our scarce resources. And to the extent that they’ve succeeded, they’ve also reinforced the canonicity of their subjects by increasing the amount of critical attention paid to them.

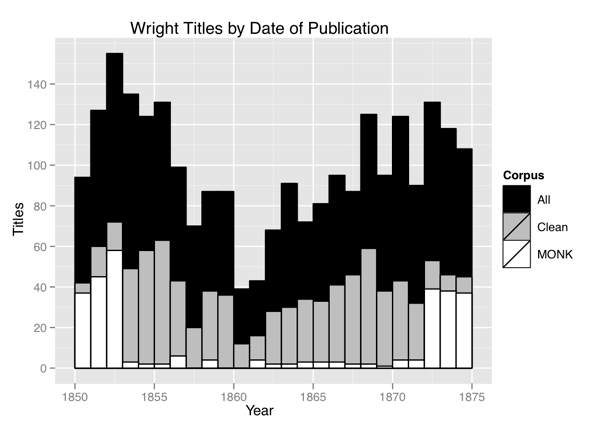

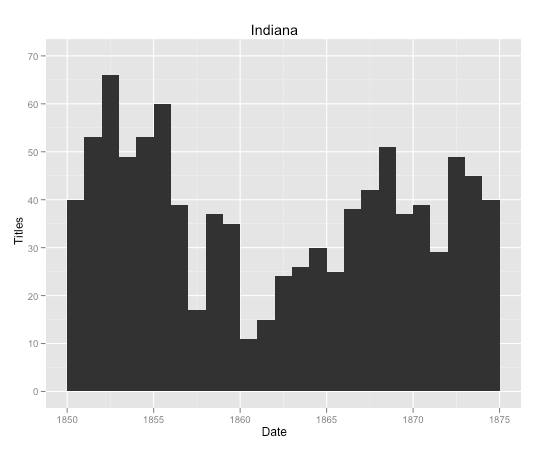

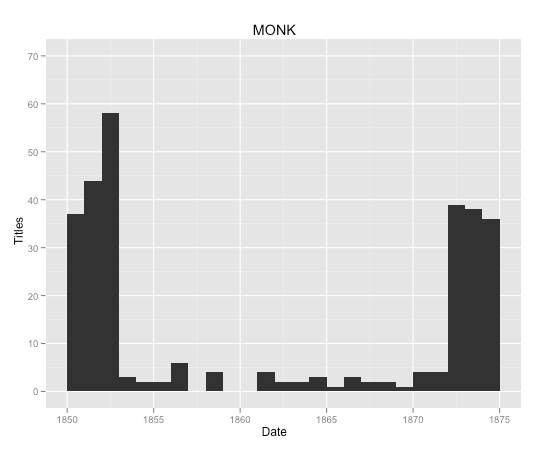

What’s required for computational and quantitative work—the kind of work that undermines rather than reinforces canons—is more material, less elaborately developed. The Wright collection, on which the 1851 map that I showed a few minutes ago was based (Figure 1), is a partial example of the kind of resource that’s best suited to this next development in digital humanities research. It covers every known American literary text published in the U.S. between 1851 and 1875 and makes them available in machine-readable form with basic metadata. Google Books and the Hathi Trust aim for the same thing on a much larger scale. None of these projects is cheap. But on a per-volume basis, they’re not bad. And of course we got Google and Hathi for very little of our own money, considering the magnitude of the projects.

It will still cost a good deal to make use of these what we might call “bare” repositories. The time, money, and attention they demand will have to come from somewhere. My point, though, is that if (as seems likely) we can’t pull those resources from entirely new pools outside the discipline—that is to say, if we can’t just expand the discipline so as to do everything we already do, plus a great many new things—then we should be willing to make sacrifices not only in traditional or analog humanities, but also in the types of first-wave digital projects that made the name and reputation of DH. This will hurt, but it will also result in categorically better, more broadly based, more inclusive, and finally more useful humanities scholarship. It will do so by giving us our first real chance to break the grip of small, arbitrarily assembled canons on our thinking about large-scale cultural production. It’s an opportunity not to be missed and a chance to put our money—real and figurative—where our mouths have been for two generations. We’ve complained about canons for a long time. Now that we might do without them, are we willing to try? And to accept the trade-offs involved? I think we should be.