The short, polemical version of my thesis is this: It can be done better. The more nuanced and accurate version is that close reading—our only real working method—has significant intellectual costs, and that we’re now positioned to reduce some of those costs if we’re willing to take seriously the opportunities afforded by digital texts.

Let me elaborate …

Here’s how nearly all of us work: We find a cultural object that we like, or dislike, or that strikes us as important. We study it closely. We note passages or images or structural features that reveal something about the work as a whole. And then we make an argument about the relationship between our object and some larger phenomenon; American naturalism, maybe, or late capital, or the Victorian public sphere. Sometimes—but not often—our argument is causal; that Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for instance, helped set in motion the events of the Civil War, or that Dickens’ style was a direct product of the economic conditions of publishing in the nineteenth century. More often, though, we treat our objects symptomatically, and address to them questions of the form “What must have been the case for this object to have been have been produced as it was?” or “What hidden features of its situation of production does this object reveal to us?”

This is all to say that we are not—and have not been for some decades, at the least—primarily aesthetic critics. Our immediate objects are aesthetic, yes, but our concerns and investments are sociocultural, political, economic, and so forth. This is a good thing, because it keeps our field from being utterly marginalized as a matter of belle-lettrism or art appreciation. More to the point, there’s broad agreement in the profession that these social and cultural questions are by far the most important and interesting ones we can address. As I say, this is all to the good.

But there’s a certain tension between our large-scale ambitions and the techniques we use to pursue them. After all, we’ve been reading a few important texts with exceeding care since Aristotle taught us how to achieve the effects of tragedy by referring to illustrative passages from Sophocles and Euripides. (NB. For convenience, I’m dropping the general “object” and “analyze” for “book” and “read,” but understand this as as a part-for-whole figure.) This makes sense: If you want to teach people to write well, you show them examples of good writing to imitate. And since most writing is dross, you can ignore the majority of it. Nor is the matter confined to pedagogy. If your aim is to say “this is good, this is art” you’ll work the same way; you don’t need to have read all the bad stuff to understand the good. In a related vein, if your task is to understand a text that you already know is important—the Bible, say—it pays to read that book closely, even if your devotion means you can’t read much else.

Two models, then, from which we derive our dominant working method: aestheticism and biblical hermeneutics. There’s nothing wrong with either of them, of course, but we should notice two things:

- They assume that there either aren’t very many books to read, or that we can get away with reading a smallish subset of a larger literary field. In other words, that there’s no necessary problem that follows from not reading everything.

- Neither one (aestheticism, hermeneutics) looks much like the kind of cultural criticism that I claimed now rightly dominates our field.

The first of these—the assumption that important books are scarce—is the reason we still have canons. If you should and can read everything, you don’t need a canon. But if you shouldn’t (because some books are unworthy, or politically suspect, or blasphemous—three ways of saying the same thing) or can’t (“because they are too menny”), then you have to pick a few to read, assuming it’s important to read in the first place. And the books you pick from any sufficiently large pool of candidates will be at some level arbitrary and nonrepresentative, if only because you’ll have read so little of the source material in the first place. This is why the canon wars of decades past were at once necessary and absurd. Necessary because it was in fact important to stop reading Dryden and start reading Morrison (synecdoches both, of course). But absurd because the idea that rearranging the canon is in any way egalitarian—it just picks new winners—or has anything to do with eliminating canonicity as such is entirely misguided. So long as we depend on close reading, we will always work on a group of texts that comes within a rounding error of nothing when compared to the full field of literary production.

[Footnote: Some quick figures and calculations. There are about 50,000 new novels published in the U.S. every year. There are 26,000 tenured and tenure-track faculty members in U.S. English departments (of which 7,000 are at R1 schools). Assume that ten percent of any English department’s faculty work on truly contemporary American fiction. Rounding a bit, that means twenty novels per TT faculty member per year, assuming absolutely no overlap. If you want to have just four other people with whom to discuss your work, you’ll need to publish on 100 new novels every year, just to keep up with the pace of literary production in the United States. Even that seems optimistic; consider the case of all English-language novels published before 1900. There are no more than 100,000 such titles, and the number isn’t growing. If 5,000 TT faculty work on them, that means each faculty member is responsible for just 20 (or 100, if we want to have overlapping coverage as above) novels over her entire career (not annually). And yet we know from experience that we haven’t dealt with anywhere near all of the novels published before 1900—not even close—over all of literary-critical history, much less during each academic generation. And in any case, this addresses the problem only at the level of the profession as a whole; it does nothing to provide each individual researcher with meaningful knowledge about the full range of relevant literary and cultural production. (Sources: R.R. Bowker, MLA.)]

Again, this wouldn’t matter so much if our aims were aesthetic or exegetical. But they aren’t. And so we have a real problem. We want to be able to claim that the books we study are representative (the word I used earlier was symptomatic) of the culture that produced them, so that by analyzing those books we are also necessarily analyzing that culture. True, this always works at an initial level: Any book is indeed a product—and a part—of a cultural situation. But it’s a minuscule part, not because books are unimportant (that’s a separate question), but because it represents so small a fraction of that situation’s cultural and symbolic output. So we need a second level of representativity, and the usual way of providing it is to argue that the book in question is especially illuminating, that it reveals something about the situation of its production that is either particularly important and typical (thus that the book is more central than others) or especially difficult to discern by other means (hence that the book is uniquely diagnostic). Either way, though, it’s hard to make this claim without already knowing, on independent grounds, a good deal about the features and configuration of the situation you’d like to say the book allows you to diagnose.

Another way of putting this is to say that literary studies as currently practiced has a problem with at least perceived selection bias. If you want to argue, for instance—and I’m borrowing from my own work here for an example that will eat up most of the rest of my talk—that allegory is a form well-suited to dealing with the problems of transitional cultural forms, and therefore that it (allegory) should play a prominent role in the literature of a transitional moment like late modernism, you’ll want to show that late modernist literature is indeed especially allegorical. You can do that by offering readings of a broad swath of important late modernist fiction—six or eight books, maybe—and pointing to the significant, underappreciated role that allegory plays in them, and then comparing these results to the standard account of modernism and postmodernism proper, from which allegory is essential absent. But you can already imagine the difficulties of this approach. What about The Bell Jar? What about other books written shortly after the war that aren’t allegories? What about instances of allegory before and after late modernism? What about Pilgrim’s Progress? Some of these questions are easier to answer than others, but they all amount to the same thing: Allegory wasn’t invented in the years following the second world war. If it’s been around for centuries, and if we know about examples of it both in and out of that period, and if you’ve read very little, statistically speaking, of the relevant literature, how can you be sure that the phenomenon you claim to have identified isn’t simply an artifact of your own haphazard selection of texts?

The long answer involves the meaning of cultural dominance, the practical and theoretical relationship between literary production and social-economic conditions, the evolution of established forms, a reasonable knowledge of literary history, and a certain amount of hand-waiving. But the short answer is that you don’t. You don’t know that any meaningful claim about the large-scale processes of cultural production is right in the sense that it describes the operations of that production by reference to the bulk of its output. And you never will, if that production occurs on an industrial scale and if you need to engage with each artifact individually and at length.

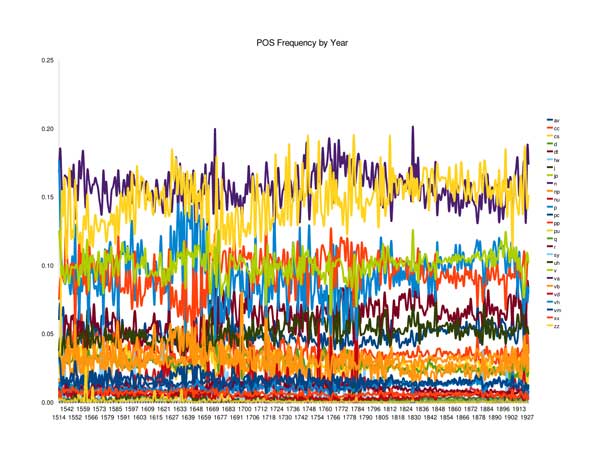

So what should you do instead, if this fact bothers you and if you don’t intend either to give up entirely or to return to small-scale, low-stakes aestheticism? One approach—an approach less insane than it sounds, since it’s really only what you were implicitly claiming in the first place—is to try to figure out how to measure allegory in millions of texts across hundreds of years. If you can do that, you’ll be able to see how the frequency and degree of allegorical fiction has changed over the last several centuries, and you’ll observe the degree to which those fluctuations correspond to our existing sense of literary and cultural periodization. If the initial claim was correct, and allegory is closely tied to eventful or revolutionary moments, you’ll expect to find something like this cartoon:

Figure 1. Allegory as a function of time (cartoon).

The best case scenario will be that most spikes in allegoricalness line up with major transitions in literary history as we now understand them (so that we have confidence that the method works and that the theoretical claim is plausibly supported), but also that a small number of them don’t correspond (so that we have new and interesting problems in literary periodization to investigate).

The problem, of course, is that we don’t know exactly what it is about a text that makes it allegorical. This is due in part to a defect in the existing conventional criticism, namely that we understand allegory much less well than we generally assume. But it’s also true that allegory is probably not reducible to anything so obvious as the frequency of intuitable keywords or the length of the text. What we need, then, is a reasonably large corpus that consists of known allegorical and nonallegorical works on which we can try out any proposed criteria. Better yet, we could go looking (pseudo-inductively) within that corpus for markers that work more or less well to separate allegory from nonallegory. But now we run up against a second difficulty, namely that there’s no ready list of allegorical books. (Note in passing that we’re therefore on different ground from Moretti and Jockers‘ or Witmore‘s work on genre determination, which relies on established bibliographies or the long-standing consensus around Shakespeare’s plays.) One could try to come up with—and to defend—such a list by hand, and it will probably be necessary to do so eventually. But that’s an extremely labor-intensive way to go. We’re looking for a sampling that covers three or four hundred years, across national origins, textual subgenres, author genders, subject matter, and so forth. If we don’t want the distinctions between allegorical and nonallegorical works to be dominated by the vagaries of selection bias (after all, that’s the problem we’re trying to get around), the corpus will need to include at least hundreds of books, maybe thousands. As I say, a lot of work.

[Footnote: Apropos our unsettled understanding of allegory, my own general-purpose definition is as follows: An allegorical text is one in which we can (and should) identify a pervasive set of figurative mappings between elements of the (independently legible) plot and elements of a coherent second plot, typically more significant (for us, the readers) than the first. The normative imperative is slippery here, of course, but I don’t see much way around it, and of course the whole thing is fundamentally context-dependent; allegory is as much about reading practices as about writing.]

What we’d like to have is a set of texts that differ only in that they are or are not allegorical, holding constant as many other variables as possible (author, subject, date of composition, and so on). That’s not likely to happen directly, but what if we compare works by the same author that fall on either side of the allegorical divide? That doesn’t do much to help with subject matter, so it’s not likely to help a great deal with keyword identification, but it controls for authorial style, gender, national origin, date of composition (give or take), and, if we’re selective, subgenre. If we can get a handle on the differences between a reasonable number of such pairs, we’ll have a start on identifying a more comprehensive set of differentiating features for allegory.

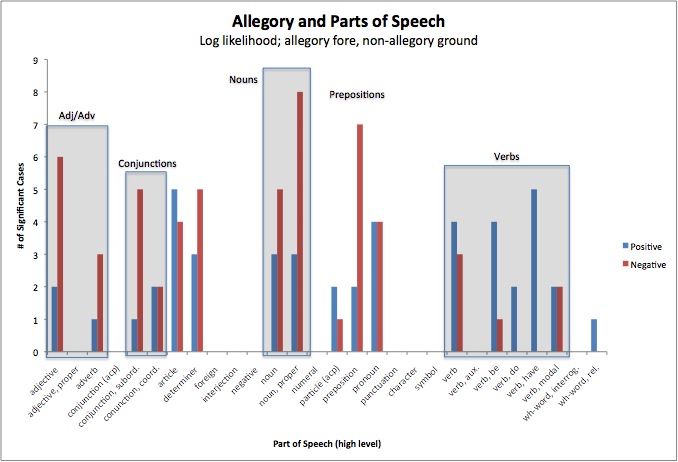

Preliminary work along these lines suggests that there’s a strong positive correlation between allegorical texts and those that are rich in verbs and poor in many of the other major parts of speech, including nouns, descriptive words, conjunctions, and prepositions. This makes decent sense; allegories tend to feature comparatively simple surface-level plots and focus on action over description, because the more complicated and specific the first-order narrative, the more difficult it is to maintain the mapping between levels that is the substance of allegory. The correlation concerning parts of speech is nowhere near perfect, of course, and analyzing it is a problem in an awkward number of variables, even before you add other potentially differentiating criteria such as keywords, common word frequencies, grammatical constructions, and other candidates for differentiating features. What’s required—and what’s currently underway—is an iterative process by which the corpus of known allegorical and nonallegorical texts can be built up in pieces and with increasing confidence. This relies on both computational methods to extract information about the texts and to weigh the various differentiating factors, and what the information retrieval people in computer science call “domain knowledge,” namely an informed critical assessment concerning the nature and function of allegory in a wide array of texts.

Figure 2. Allegory and parts of speech in single authors, demonstrating the number of pairings in which each part of speech was a significant differentiating factor. Blue = positive association with allegory, red = negative. Method of comparison is Dunning log likelihood.

This is slow going, in a way: Applying descriptive statistics and information retrieval techniques to literary text analysis isn’t something that’s widely practiced or about which there’s much prior work to consult. And the less said about copyright and twentieth-century texts, the better. But because the process builds outward from close readings of a few dozen novels, it’s much faster than dealing with hundreds, thousands, or millions of novels individually. More importantly, once it reaches a critical mass past which we are confident of our ability to classify allegorical and nonallegorical works algorithmically, it can scale to arbitrarily large corpora with minimal effort. And that’s really exciting. Recall what’s happened here. We started with a problem that we simply couldn’t address, namely how to say something informed about the enormous range of literature that we can’t read. We had a conventional theoretical and literary-historical argument that was impacted in an important way by this problem. By introducing computational methods, we now have the ability to overcome this limitation, and to do it in a way that extends and augments (rather than replaces) our existing analytical techniques.

[Footnote: It’s not quite right to say that statistical-computational work in literary studies is entirely new, and I don’t want to be accused of forgetting several decades of progress. But I also don’t want to speak the name of authorship attribution, and I don’t see how you can do the former without the latter, at least not in a short paper whose main concerns lie elsewhere. See Martin Mueller’s excellent analysis of the problem, which does this work so I don’t have to.]

Even if you don’t care much about allegory in particular, this example should appeal to you. The idea isn’t, of course, either to replace close reading entirely or to replace ourselves with computers as the ones doing the close reading, but instead to offer a new kind of evidence that’s especially well suited to supporting the kinds of extracanonical cultural, historical, and sociological claims that have come to occupy a central place in the discipline over the last few decades. Insofar as computational methods like the ones I’ve described today advance this cause—and because we know only too well the limitations of our existing method—there’s little doubt that digitally assisted criticism can and must play a much more important role in both the immediate and long-range future of literary studies. We have only to begin doing it.

Postscript

The focus to this point has been on the movement “outward” or “upward” from individual texts toward large-scale social and historical issues understood through variations in large literary corpora. Computational methods are well suited to this type of scaling, since computers do simple things like part-of-speech recognition quickly and uncomplainingly. But the process can and does work in reverse, something I suggested elliptically through the interplay of machine learning and domain knowledge. To be more explicit, though, we can imagine a case in which computationally derived information about the prevailing level of allegorical usage in a given period would allow us to identify, for instance, the unexpectedly anomalous allegorical bent of an author not usually understood to be an allegorist. This is turn might point us to a new reading of that author’s works, or of her relationship to the dominant modes of her age. Or our attention might be drawn to an author’s work that scores especially highly or anomalously in allegorical terms, but that has never before been given critical attention.

More concretely and in a different area, what if statistical analyses of Shakespeare’s texts suggest that Othello looks much like a comedy? This certainly doesn’t mean that Othello is a comedy, but it might give us new reasons to return to a well-known text and to ask of it different questions than those we posed in the past. The results of our new line of inquiry may or may not be interesting; only time and analysis will tell. But new ways of approaching Shakespeare are probably a good thing, as are procedures that allow us to pluck interesting works from obscurity for guided critical attention. And both of these are examples of the “inward” or “downward” orientation that computational work also serves.

[Note, 24 May 2010: This is a lightly revised version of my talk for the 2009 MLA conference in Philadelphia.]