A few days back, I tweeted about the Racial Dotmap, a really cool GIS project by Dustin Cable of the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at UVa. The map shows the distribution (down to the block level) of US population by race according to the 2010 census. There’s a fuller explanation on the Cooper Center’s site.

The map is fascinating stuff — I lost most of a morning browsing around it. Really, you should check it out. To give you an idea of what you’ll find, here are a couple of screen grabs:

The eastern US (click for live version):

South Bend, Indiana (with Notre Dame). Not clickable, alas, but you can find it from the main map:

One of the things that’s especially appealing about the project is how open it is. The code is posted on GitHub and the underlying data comes from the National Historical Geographic Information System. That fact, along with a suggestion by Nathan Yau of FlowingData, made me wonder how much effort would be involved in creating a version of the map that would allow users to move between historical censuses. It would be really helpful to have an analogous picture for the nineteenth century as I work on the evolution of literary geography during that period.

If I were cooler than I am, this would be where I’d reveal that I had, in fact, created such a thing. I am not that cool. But I wanted to flag the possibility for future use by me or my students or anyone else who might be so inclined. I’m thinking of at least looking into this as a group project for the next iteration of my DH seminar.

I can imagine two big difficulties straight away:

- You’d need to have historical geo data, particularly block- or tract-level shapefiles. I have no idea how much the census blocks have changed over time nor whether such historical shapefiles exist. Seems like they should, but …

- You’d need the historical census info to be tabulated and available in a way that allows it to be dropped into the existing code or translated into an analogous form. I haven’t looked at that data, so I don’t know how much work would be involved.

Anyway, the Racial Dotmap is a great project to which I hope to be able to return in the future. In the meantime, enjoy!

Update: Mostly for my own future reference, see also MetroTrends’ Poverty and Race in America, Then and Now, which focuses on people below the poverty line and has a graphical slider to compare geographic distributions by race from 1980 through 2010. Click through for the full site.

digital humanities blog @UChicago

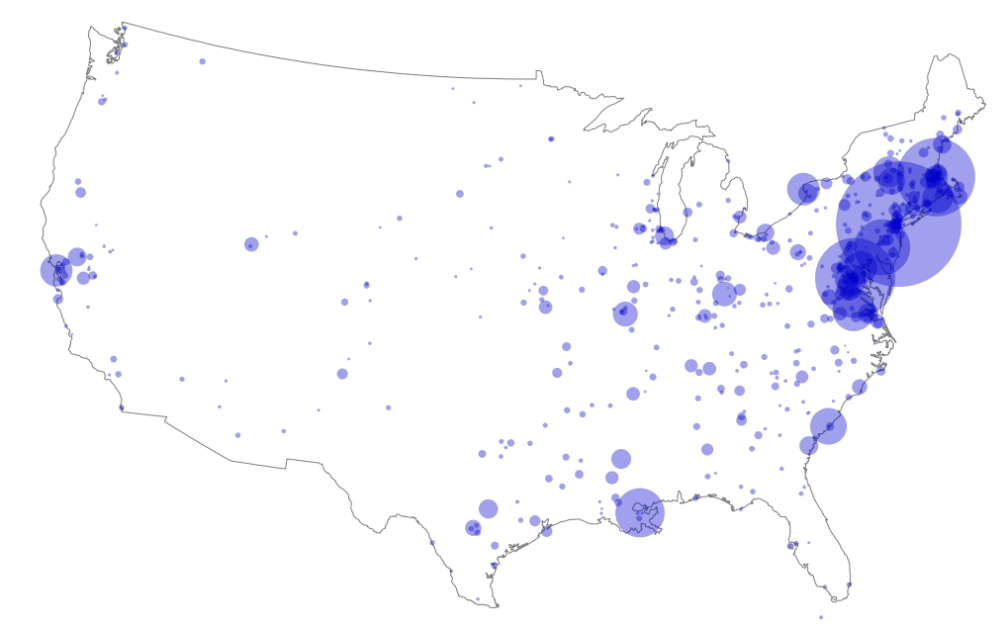

The distribution of US city-level locations, revealing a preponderance of literary–geographic occurrences in what we would now call the Northeast corridor between Washington, DC, and Boston, but also sizable numbers throughout the South, Midwest, Texas, and California.

The distribution of US city-level locations, revealing a preponderance of literary–geographic occurrences in what we would now call the Northeast corridor between Washington, DC, and Boston, but also sizable numbers throughout the South, Midwest, Texas, and California.