Elizabeth Evans and I have a new article, “Nation, Ethnicity, and the Geography of British Fiction, 1880-1940,” out in Cultural Analytics.

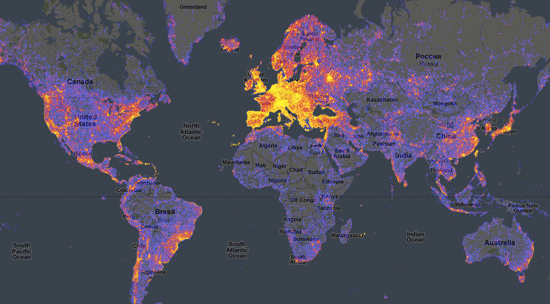

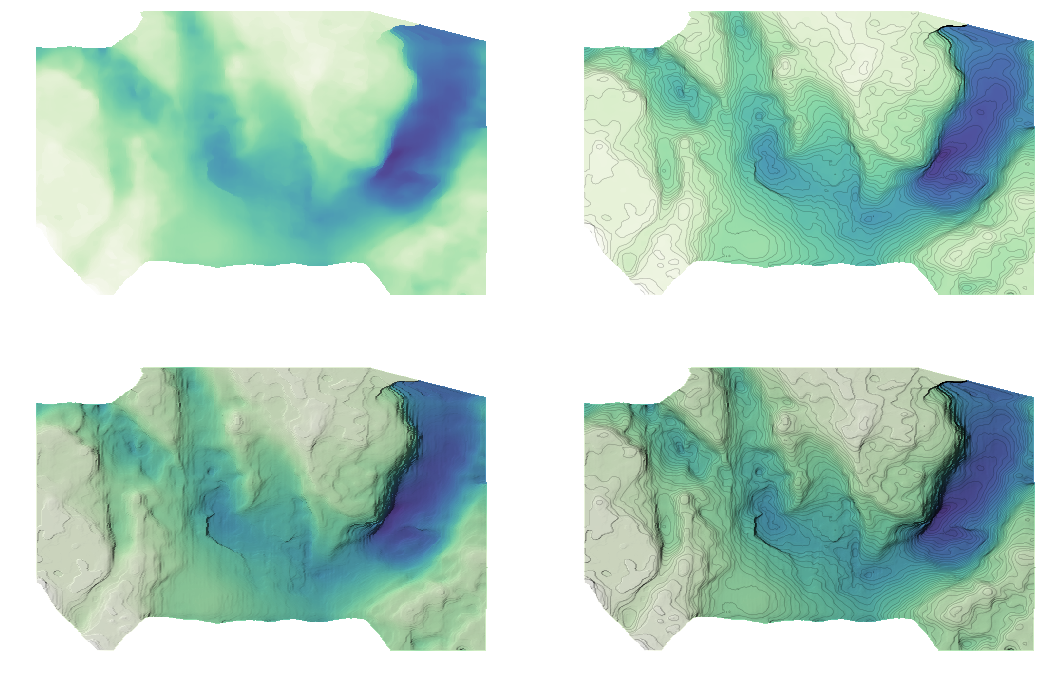

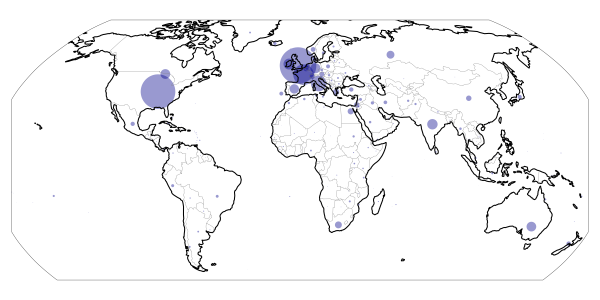

It’s a lengthy, data-driven exploration of the literary geography of British writing during the modernist era, but it’s not really about modernism per se. We compare geographic usage in books by well-known writers to that in books by mass-market and colonial authors, and we spend some time trying to assess how British literary geography changed over six decades.

A few highlights:

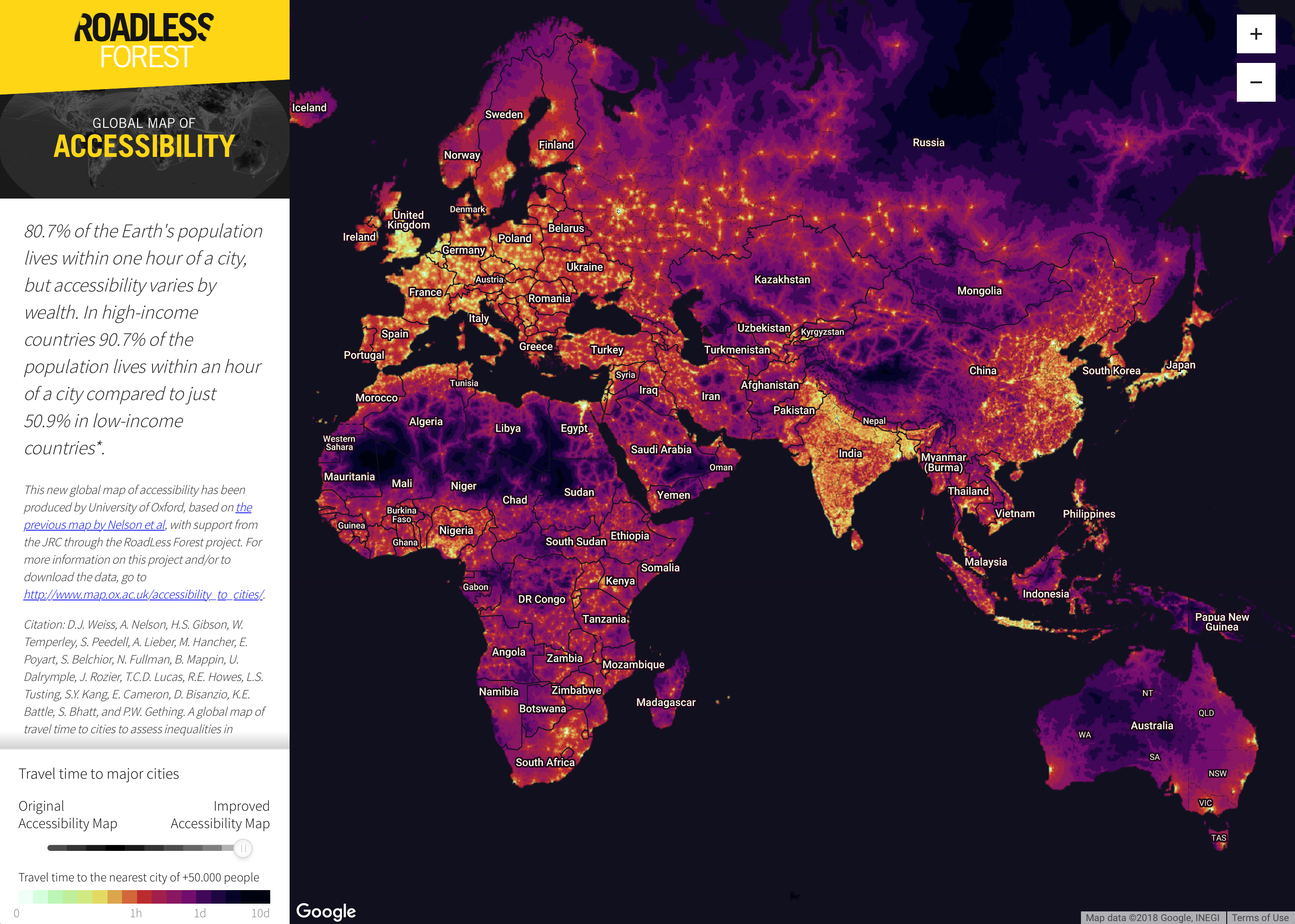

- Books by famous writers — including canonical modernists — became more international over time. But they lagged the international attention of mass fiction by a decent amount and that of foreign-born writers by a lot. If critics are interested in modernism in part because it was less domestic and provincial than Victorian lit, they could find even more striking examples elsewhere.

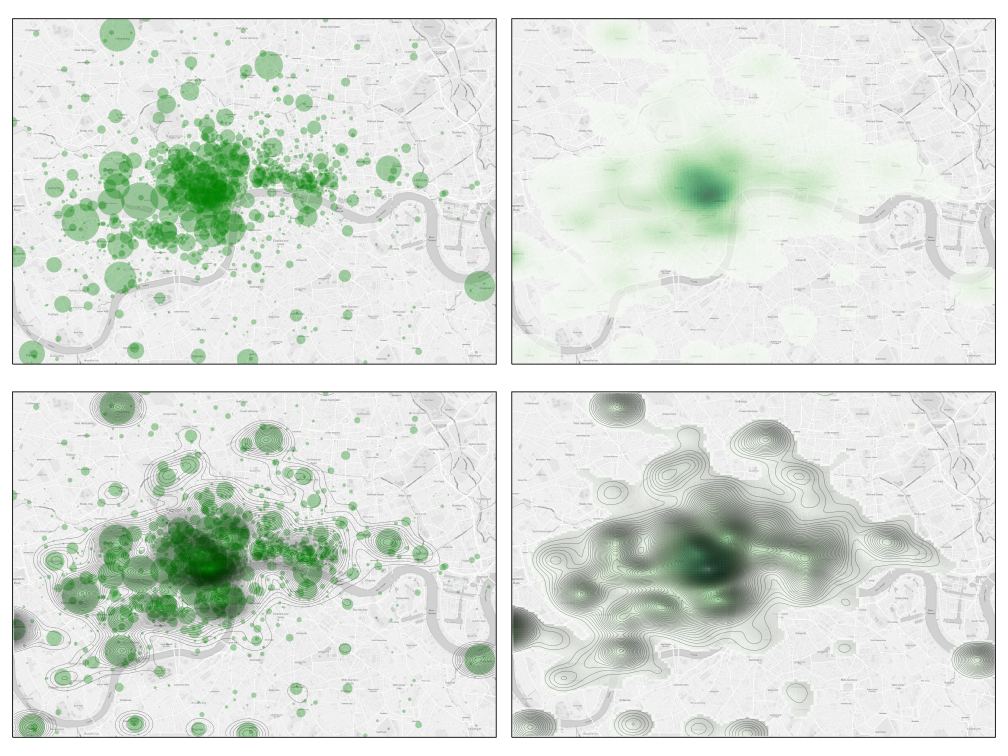

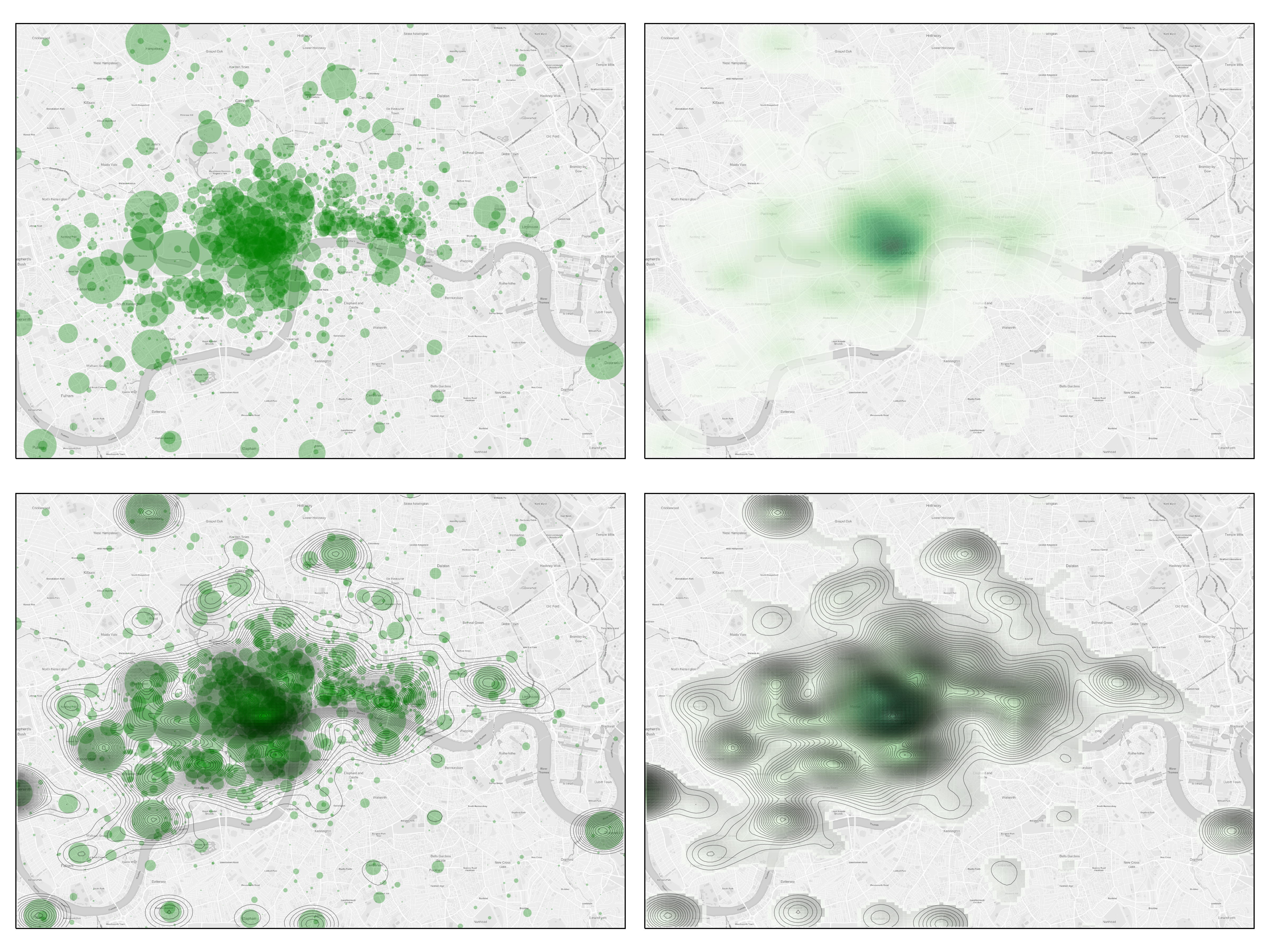

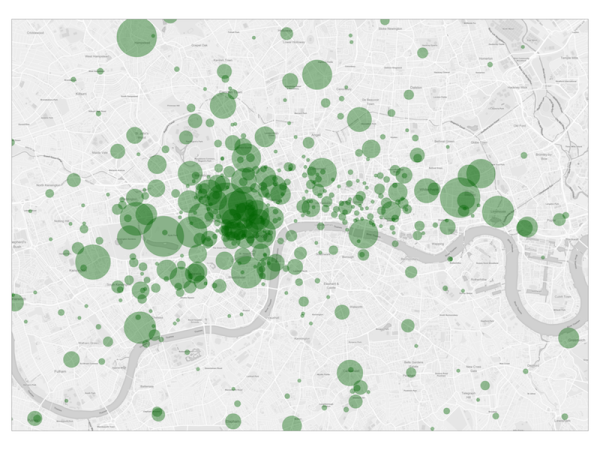

- Foreign writers of color devoted much more of their London attention to parks, rivers, and other green spaces than did other groups of writers. No such effect for foreign-born white writers. A concrete effect of differential social access to domestic and commercial spaces?

- London really dominated British domestic attention, even more than the population of the city would suggest. The U.S. case is different. We’d love to have comparable data for French lit.

- There were significant differences in the specificity of geographic usage between groups of writers. Foreign-born authors used many more non-UK places, but they were more likely to favor higher levels of abstraction (“India” rather than “Delhi,” for example). We think this is tied to social and political content over against setting and characterization.

- We don’t find evidence of any strong, across-the-board uptick in geographic use during the period. But it’s not hard to find select places that were used more intensively after, say, WWI, and therefore not hard to see how the impression of a geographic turn could have taken hold.

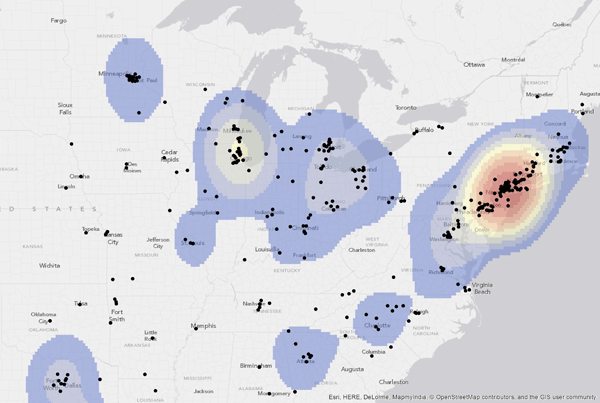

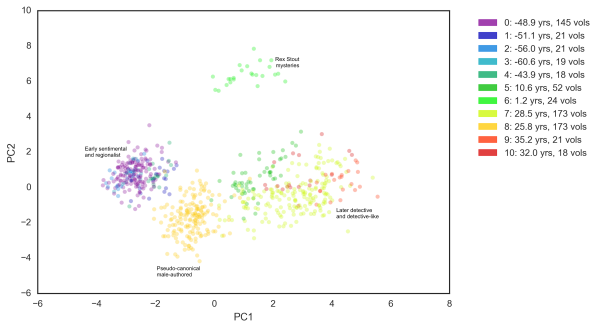

- You can explore an interactive visualization of authors’ geographic similarity.

Here’s how we frame the intervention in modernist studies:

Our results lead us to three broad interventions in modernist literary studies. First, we argue that a modernist studies that values internationalism must devote significantly more attention to non-canonical literature. The mass run of fiction published between 1880 and 1940 was consistently and meaningfully more international than its better-known analogues. Writing by non-native British writers was radically more so. If critics are drawn to the outward turn in modernist texts, they can and should find a larger, earlier, and perhaps more important version of the phenomenon by looking beyond the usual suspects.

Second, we need to rethink London as it was encountered and described by outsiders. This isn’t just a matter of turning away from the famous and the posh in favor of the neglected and the downtrodden (though there are worse places to start). It’s about explaining, for instance, why foreign writers of color depict a more public, verdant London than their colony-born white counterparts, while devoting less of their attention to the East End and to notably international districts of the city. These patterns are either anecdotal or essentially invisible to conventional study. Computational methods make them available for nuanced literary-historical reinterpretation.

Finally, we argue against treating the years between 1880 and 1940 in terms that emphasize temporal discontinuity. Aspects of British fiction did change across this span of sixty years, and many of the differences we observe in the era’s literary-geographic attention are genuinely important. But when we work at scale, it’s very difficult to locate “on or about …” moments of sudden change across whole ranges of texts. We see instead situations of influence and drift or—and this is the rub—we find true ruptures only between corpora built around differing principles. The latter case, comparing corpora assembled to emphasize difference, is the one that resembles most closely the way in which modernist studies built its canons. Those canons and the practices they embed aren’t simply errors, but they are deliberately and systematically nonrepresentative of large-scale literary history. Modernist literary critics would do well to grapple with that fact more directly than we often have.

There’s a lot more in the article, and the underlying code and data are freely available. Check it out!

Ours thanks to the NovelTM group, where we first workshopped the paper; to Stephen Ross, who offered helpful feedback on the manuscript; and to the NEH, which supported our work via a grant to the Textual Geographies project.

The

The  I’m pleased to announce that the

I’m pleased to announce that the

New year, catch-up news. I have an article in

New year, catch-up news. I have an article in